Habits are hard to break. It is difficult “to go against the grain”.

The scribbler gum trees near the beach all bend with the prevailing wind. The “habitus” (the natural inclination) of the tree accommodates to the prevailing conditions.

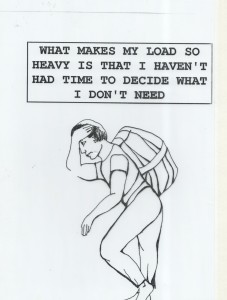

We are no different. If we are regularly blown over by criticism, and, particularly bowled over by our own self-criticism and our negative self-talk, our habitual stance in most areas of the “self” will be to be borne down by distress. In our posture we are bent over by misery.

Self-identity is crushed, significantly lost. Our identity and our efforts are ruptured under the burden of low self-esteem and brittle self-image. This stance in life will be reflected and projected out in life as a lack of liveliness and lost elasticity in our posture and gaze. People around us will read our posture and general body language as conveying a poverty of energy and a paucity of interest. The feedback will be disinterested reactions towards us from other people. Our seeming lack of energy and interest goes nowhere, in turn, in energising other people close to us to interact with us.

The low level of energy reflected back to us validates and reinforces the original negative self evaluation and misery. This type of spiral of negative psychosocial reinforcement is a twister of a storm. In terms of our mental health this reciprocity can result in an extra load of anxious depression.

Recently, I attended a conference “Dialogues in Depression” in Sydney. As a first time for me, I heard an international psychiatrist provide a central place in his keynote address for recognition of the process of neuroplasticity. The 21st-century has already approved of neurocircuitry with information processing and the fundamental flexibility of brain (neuro-) plasticity as a basis for generating new psychiatric treatments particularly for depression and pathological anxiety. These key ideas also fuel further attempts to evaluate earlier established treatments. The catecholamine theory which has generated 40 years of pharmaceutical treatments in psychiatry along with exploding knowledge about synaptic neurotransmitters has been degraded to a position of past practical importance. However, this well-documented theoretical approach appears to have little relevance in generating contemporary treatments.

Dr Norman Doidge notes that his first book, The Brain That Changes Itself, celebrated the end of the struggle to announce the discovery that the brain is malleable, changed by experience and neuro-plastic. His new book The Brain’s Way of Healing published recently notes the progress of treatment based on intrinsic properties of the brain involving essential remodelling of neurocircuitry and information nodes. The remarkable discoveries involving neuroplasticity point the way to significant new therapeutic methods. These new treatment possibilities will be based in the changes in neurological structure and functioning reactive to habitual activities and mental experiences. Fifteen years ago the Nobel Prize in physiology recognised the Association of activity-related provoked connections between giant cell neurones in response to active learning (discoverer Eric Kandel). Our brains progressively change and adapt to accommodate an internalised map of our world of experiences.

We are, indeed creatures of habit.

Our nervous systems are plastic organs which form, reform and deform to reflect and to accommodate the prevailing conditions and the feedback experiences which we have. Like a politician flying a kite, we accommodate to the prevailing climate of opinion. This is not remarkable. Even the scribbler gum trees along the coast do it. These gum trees live in an environment where there is a line of force from the wind across a particular axis of growth. The internal structuring of plant growth ultimately follows the force lines within which the tree is living. The tree has internalised, within its form, the environment in which it is living.

We too make sense of the world by internalising a model of the world which is encoded into circuitry pathways within our nervous system. We can find our way around a familiar house in total darkness because we have a map of the house in our head.

Sometimes we can remember the pin number for our ATM cash card by shutting down the mind and just letting our fingers walk over the keypad.

Part of our model of the world is the model of our self-image and self-esteem. This explains why we can have phantom sensations in a limb which has been amputated.

If our model of self is faulty or painful, it can sometimes take too much effort and time to readjust. This is particularly so if the people around us have so adjusted to mislabelling us that we continue to receive painful and self-defeating feedback which might no longer be deserved or relevant.

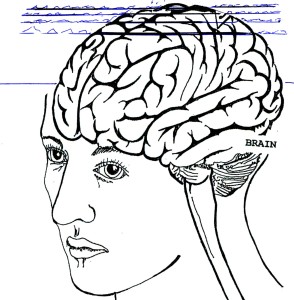

Consciousness that is self-consciousness arises out of the plasticity of the infantile brain as the child grows, matures and learns. The growing brain is shaped by this learning and islands of knowledge regarding the self and the world develop in stages.

The brain progressively emerges from the ocean the creation; first as islands of limited awareness, then followed by the coalescing of islands into continents.

Finally, the supercontinent of the cerebral cortex emerges. (Note the diagram below with lines across the top of the brain indicating the ocean and the first emergence of an island or two and then the progressive revelation of the cerebral cortex in all of its beautiful organisation and functionality

As we age and development, the islands develop and coalesce into a continent upon which we draw, within the giant cell cerebral neurones of the cerebral cortex, our three-dimensional road map of the world. This mental imaging includes the relationships of each thing and person to the other in that world. This is particularly applies to the social and to the psychosocial relationships within the world which we internalise.

We literally take inside us within our own nervous systems the three-dimensional map of our own place in the world. If our map misdirects us, we lose track of self-identity and self-image. The experience of self-esteem is therefore downgraded. We become lost in a self mired in a minefield of doubt and distress.

There is some good news. When we do that, we are not setting our own insecurities in cement. It is now known that the brain is plastic and can be re-modelled and rebuilt over again by experience.

However, spend a few decades modelling inside your head self-images and a total self-identity which are negative and uncomfortable and the total complex becomes very difficult and slow to alter. The mere fact of having an internalised image of our self and our role in the scheme of things determines how future social interactions are to be interpreted and played out. So the person with the negative self-evaluation is more likely to continue to run into negative experiences which reinforce the negativity of the original dubious self-estimation. As time passes, it becomes increasingly difficult to up-regulate the pessimistic original self-image.

Positive corrective experiences are hard to come by when the outcome of a novel experience for the self re-evaluation is already predetermined by an answer already locked in the head. It is necessary to go repeatedly through a great deal of pain and disappointment often with a guide/counsellor to reassure us if we are to alter our negative habitual responses despite the internal predictive pessimism.

We live in the world and our individualised world lives in us alongside our self-modeling, women positive or not. Our experiences determine what the internal self-comfort is to be and how self-identity, self-image and self-esteem are to be maintained or to be modified over the course of a life. But the original self-modelling enforces to a large degree what the repeated experiences will be.

It is a sad fact that we live life with a belief that our lives are spent within free will surrounded by wonderful choices available to all. Not so. We live our lives largely on a reflex level doing most of the things, which inform our self identity and self-esteem unconsciously.

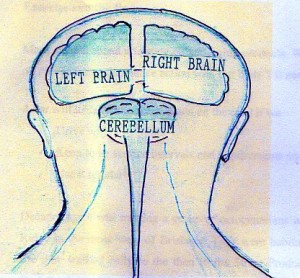

We live our lives and experience a consciousness on self largely built on a process involving “automatic pilot”. Most of our activities of daily living and many other choices and reactions go on within the cerebellum which sits at the base of the brain. If this were not so, there would be little room within the cerebral cortex for us to do the scanning and the more creative elements involved in discrimination and thought.

Only a few decades ago, the cerebellum was thought merely to be an organ of balance.

We now know that the cerebellum has one quarter of the total number of giant cell neurones when compared to the two cerebral hemispheres.

VIEW FROM THE REAR OF THE SKULL

THE CEREBELLUM IS POSITIONED AT

THE BASE OF THEBRAIN.

It sits on the back of the hind brain between the

spinal cord The Cerebellum possesses1/4 of the

brain’s giant cell.Neurones. The

Therefore, structurally and by its position,

the Cerebellum is the ideal organ to run

programming unconsciously for behaviours and

habits which have necessarily or incidentally

become automatic.

The cerebellum has 25% of the number of the giant cell neurones yet, it has more wiring and connectedness than the rest of the total nervous system altogether. In fact oddly, the cerebellum puts everything in the nervous system into balance. It ties together the whole neuronal system and then runs our lives essentially on automatic. We cannot play piano, type on a keyboard, drive a car, swim and so on until the cerebellum has been programmed to do the activity thoughtlessly.

“Thoughtlessly”. This is a key word. It explains why many people believe that we cannot change our habits. Of course, we can work on ourselves. But we had to think and behave in a deeply aware manner in order to overcome the basic automatic nature of life. The subconscious are known large part of the brain sits quietly as an apparently thoughtless part of the nervous system. But it is not inactive. The unconscious (discovered by poets historically and later officially more than 100 years ago by Freud and Carl Jung is monitoring and absorbing all of our experiences and programming our automatic emotional and behavioural drivers within. The experiences which we take on board thoughtlessly may be beyond thought. But thoughtless, reckless experiences are still influential. Negative self-talk, bad choices, bad actions, poor attitudes, negativism; — all these are monitored and programmed by the nervous system and automated in the cerebellum.

We must presume that experiential activity is being adapted at a basic level despite our sometimes less than appropriate habits. Thereby, we are unconsciously adapting to and accommodating a world which is ever-changing. Indeed, we are upgrading our habitual attitudes and our unconscious behavioural repertoire constantly without even realising it. Our habitual activities, secrets, negative habits are written down in a nervous system in the language of our image of the world and in line with our operating self-image of the time.

It is known out that if we eat junk food regularly, we literally become what we eat. Eat takeaway hamburgers endlessly and your physical self may ultimately resemble the hamburger. If we think rubbish; if we rubbish what we think, we build up relative misery within a deformed self identity and within a maladaptive self-image and allow the persistence and growth of negative self defeating set of habits.

Living life with a negative self-evaluation, a negative self-identity, is like carrying a huge load of depression, pessimism and selfdefeat around continuously. Our self-talk (the internal dialogue which we all carry on in our cortex) becomes even more oppressive than that of the average human being. Other people around us pick up on our own negativism and then reflect it back to us. People will demonstrate interest in our unconscious failure without being able to or even inclined to offer assistance. The outside world mirrors ever more closely the negative in a model which we are automatically embracing and thereby regularly remodelling to our detriment.

We feel prosecuted and persecuted by our experiences. It feels as if the whole world is against us

What to do? This was summed up very simply by the American Cardiologist and guru of road running exercise Dr George Sheehan who said that we should “first be a good animal.” What did he mean? He was saying that we should develop good habits. Habitual life is made up of good choices regularly and consistently made. “Small steps.” But good ones.

In this sense, the simplicity and the straightforward nature of good choices built on good choices and expectations amount to the old adage, “Keep it Simple.”

Many of us spend a fortune on anti-aging products. Why not spend a little time on our bodies? The human body needs maintenance and use. We are absolutely “creatures of habit”.

Your car will usually not break-down on the road if you:

• drive within its limits

• keep to service intervals and requirements

• use it regularly.

Decades ago, I was treating a group of octogenarians who lived on the Auchenflower Ridge in Brisbane. They were habitual walkers. Earlier in life, they walked daily to the Roma Street Markets near the railway station in the city. There, they purchased fresh produce, conversed and generally socialised. They lived long and well with slow heartbeats and were:

• always curious about life

• humorous by nature

• fatalistic

• actively living day by day.

The “habitus” of the 80-year-olds was spare and straight up and down. And, they were “fit for life” within the limits of their age. Dr George Sheehan, American cardiologist, showed that lifelong activity (athleticism) preserved aerobic capacity. His motto, the neglected cliche, “Use it or lose it.”Northern European studies demonstrate that students who are active physically grow their minds better. They demonstrate this by achieving higher academic results.

Northern American research illustrates that a gym membership, actively pursued, is equivalent to a course of anti-depressants.

In sum, lifelong exercise means:

• better study when young

• the possibility of effective intimacy as an adult

• more productivity generally

• stronger bones

• preserved cardio-lung fitness

• a brighter outlook

• fewer of the sludge-up and rust-out type diseases

• possibly a better death. With your boots on!

Now the era of remodelling brain circuitry and recognising the plasticity of the neural structures of the brain indicates that, just as with habitual physical activity within which the body adapts positively, the brain can also be remodelled by persistence, effort and constructive experiences.

Good habits start now, whatever your age. Great-grandmother said that we should live life through healthy minds and healthy bodies. What is it that we have forgotten about that simple wisdom of the ages?

Postscript

If my (above) discussion with explanations of brain function has made sense to you, you may even have “internalised” ideas about mind body and the human spirit which embraces change.

The next article to be published will provide you with simple mental exercises together with ATTITUDE! Human resilience has been researched for nearly 50 years especially by Western military organisations. My approach works, I know, as I have been using it for nearly 40 years myself.

Dr Ian Curtis is a senior psychiatrist in full-time practice in Brisbane. Dr Ian Curtis is also a public speaker with over 30 years experience. Dr Ian Curtis as been involved in preparing and presenting workshops and lectures for Queensland Health, the Queensland Police Service, the University of Queensland Medical School, and Brisbane Churches. He has also lectured at international venues in China, India, and the USA.

Dr Ian Curtis is a senior psychiatrist in full-time practice in Brisbane. Dr Ian Curtis is also a public speaker with over 30 years experience. Dr Ian Curtis as been involved in preparing and presenting workshops and lectures for Queensland Health, the Queensland Police Service, the University of Queensland Medical School, and Brisbane Churches. He has also lectured at international venues in China, India, and the USA.